- Home

- Laurent Boulanger

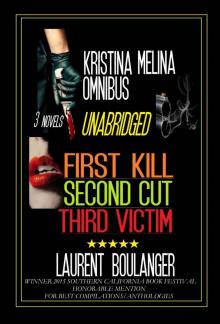

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 10

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 10

Every government department was a cobweb of fat cats and rules designed to serve those in power. From the day we went to school, we were talked down to, as if we knew nothing from right and wrong, as if we were incapable of deciding for ourselves. And now that I was a mature woman, I found things had changed little.

Sitting behind that desk, next to Frank, in front of Trevor Mitchell, made me want to pop a gasket.

But I knew better.

Although I hated the bureaucracy of the VFSC, I cared a lot about my work. My career was the only thing which kept me sane. The only reason why I wasn’t locked up somewhere where they throw the key away forever because some damn relative decides you’re not mentally fit to be let out in public.

Solving homicides made me sick but gave me a place in this world. And belonging somewhere was a basic human need, as basic as feeding and reproduction.

When people were isolated, psychotic and sociopathic behaviour settled in instead. Criminals were waste by-products of a civilised society, the unwanted, those who had no worth in the community, those who needed to be heard but were ignored instead.

As I stood up from my chair and smiled at the Director of the VFSC, I understood perfectly the criminal mind.

However, I knew I would never be able to do what they did as long as feelings of empathy were still attached to my brain. And I guess that was the main difference between us and them. We all had crazy thoughts of popping the guy at the traffic light because he stuck his middle finger up at us. But that was as far as it went. We obeyed our own imaginary, do-not-cross, white line. Sociopaths obeyed a broken, white line.

They could cross it now and then.

When Trevor Mitchell finished with us, Frank and I went for a coffee at the VFSC staff room.

The room was filled with people from various departments having their ten-minute break or early lunch. Students and police personnel who attended courses offered by the VFSC were also present.

We both bought a coffee and sat quietly opposite each other for a full minute, unable to discuss our present situation.

I broke the silence after my first sip of coffee, ‘You haven’t told me about Teresa Wilson.’

Frank looked up slowly, and I could tell he’d been taken by surprise.

‘Told you what?’

‘What you’re doing with her?’

He shook his head from left to right. ‘What are you, the thought-police or something?’ He was still worked up from the meeting in Trevor Mitchell’s office.

‘I just don’t want you to get hurt.’

‘Thanks for the concern. But you’re not my mother, and I think I’m old enough to make my own decisions. And anyway, I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.’

I leaned forward, spilling some of my coffee on the white Formica table. ‘Don’t jerk me around, Frank. I saw the flowers in her room this morning.’

‘So?’

‘So, she told me,’ I lied, hoping to God I was on the right track.

He froze for a few seconds and then stood up, sending his chair flying a meter behind him.

All eyes in the room turned to us, and I felt redness on my face.

‘Fuck you, Melina. I don’t have to put up with this shit.’

‘You don’t have to be so —’

‘Yeah, whatever,’ he interrupted. He turned to all the eyes in the room. ‘All right, the show is over. Do you mind?’ And then back to me. ‘The last time I checked with you, you were not interested. So what’s all the concern now? You think I can’t hold my dick straight or something? Is that what it’s all about?’ He jabbed his finger in the air, right in front of my face. ‘Let me tell you something, Melina. People are starting to talk around here. They think you’re losing it. You’re cracking up. All these years of homicide investigations are finally playing with your head. And you know what I think?’

I stared at him, shocked and puzzled by his personal attack.

‘I’m beginning to think they might be right. Because right now, what I do know is that my private life is none of your business. Have we got that clear?’

I maintained my composure in spite of feeling deeply hurt. I glanced around, but everyone in the room pretended not to pay attention.

Frank and I had been friends for a very long time, and he never spoke to me that way. I might have got a bit personal, but was that a reason to judge my whole career? And what about this rumour going around? Were people really talking about me that way? I knew I needed a holiday, but was it so obvious?

‘I’m sorry,’ I muttered. ‘You’re right. It’s none of my business. I won’t interfere in the future.’

‘Yeah, well, you better not,’ he commanded as he left the table, his coffee virtually untouched.

CHAPTER EIGHT

When I got home later in the evening, I drank half a bottle of Southern Comfort. Just as well Michael had gone to his friend’s place for the weekend.

A dark night filled my evening and my soul. I felt as if I’d reached the end of all meaning. No matter how I turned everything in my head, I knew I was heading for a disaster. The VFSC and the CIB were on my back, and I had just turned Frank into an enemy. For a brief moment, while the alcohol simmered in my brain, I wondered what it’d be like to lecture full time at university. The pay would certainly be better.

I should have gone to the gym to release my frustration. I seldom touched alcohol, and this binge wasn’t going down well.

First I cried myself dry, cursing my parents, my childhood, my world, Frank Moore, Teresa Wilson, Trevor Mitchell, everyone at the VFSC and the CIB, and later myself.

Then the lounge room spun in my head, sending chairs and tables and everything in sight around the ceiling, across the room, in and out of my brain.

My nerves were raw, and I was a total mess. I couldn’t remember feeling so low, ever.

I tried to sleep it off on the couch, but it was impossible. Round and round it went, until I truly believed my heart was going to burst out of my chest. I swore out loud that if I ever got back to normal again, I would love trees, birds, traffic, Frank, and everything else I took for granted.

I crawled down from the couch and into the bathroom.

I just wanted my life back, but instead I was hunched over the toilet bowl, emptying the contents of my stomach, feeling useless, miserable and stupid.

I wanted to call Frank and tell him what he had done to me. I wanted him to feel guilty, to understand what a complete jerk he’d been. But I couldn’t do it because, in spite of being off my head, I knew I was the one who’d been a jerk.

I walked up to my study, threw open the top drawer of my filing cabinet and removed the Jeremy Wilson file. I flicked through the photos I took at the crime scene, and the only good that did was send me back with my head down the toilet bowl, looking at the world at angles I had never experienced before.

I lay on the couch in the lounge room for the next twelve hours, and I swear to God, I really thought they were my last twelve hours.

Late Saturday morning, I was level-headed enough to open the balcony of my apartment and take in some fresh air. The sky was overcast, and I wished it would rain. It seemed the most beautiful day in my life, in spite of feeling as crook as a dog. I loved this city, the trams down Chapel Street, people arguing, pigeons responding to their calls of nature on my car.

I stood on the balcony for a good hour, gently experiencing flashbacks of soberness. I knew I would never again be able to touch a drop of Southern Comfort. Just the smell would send me into a violent fit of near-hysteria.

I took a shower, letting the hot water sooth my cranium, feeling my raw nerves slowly coming back to their natural function.

After a cup of black coffee, no sugar, I strolled pass the study and noticed the mess I made the previous day. The Jeremy Wilson file was open, and photographs were thrown all over the floor, the desk and the filing cabinet. I didn’t remember my act of terrorism, but since there was no one else who lived in the

place, it had to be me.

I collected various photographs from the floor, realising I should really have handed over the entire file to the VFSC for their records. And frankly I’d had a gut-full of this investigation. They could have the entire damn case, for all I cared.

As I randomly collected the photographs from the floor and threw them back in the file, something caught my eye.

I sat at the chair behind my desk and looked closely at a crime-scene photo taken at the Wilson’s apartment. I studied it for a full minute, like only drunks can, trying to recall the chain of events which led to Jeremy Wilson’s death. Something in the photograph intrigued me. Being half sober, I lacked confidence in my forensic analysis, but even if I had been sober, I still needed a second opinion.

I picked up the telephone and punched John Darcy’s mobile number.

John was a forensic biologist at the VFSC.

John Darcy was kind enough to see me at lunchtime in his home. When I got a hold of him on the phone, he was with his son at footy practice.

John only lived twenty minutes away from me in Mt Waverley.

When I needed straight answers without all the bureaucracy, I dealt directly with John, especially if the information I required had nothing to do with laboratory analysis and more with another expert’s opinion.

When I arrived at the suburban two-storey brick-veneer house, a thick manilla folder tucked under my arm, John was watering the front yard. It looked as if it was about to rain any second, but I wasn’t going to question his motive. Some people watered the garden every weekend out of habit, not necessity.

John looked younger than his fifty-two with his blond locks and sparkling blue eyes. Like me, he hated office bureaucracy and was also willing to help a fellow scientist whenever the need arose.

We made small talk in the front yard before he led me inside his home.

Mrs Darcy was making lunch for their three children, a nine year-old boy with the same hair and eyes as his father, and two three-year-old girls, who were miraculously born two days apart.

My eyes circled the lounge room to observe the inside of a typical suburban home. Family portraits hanging on the walls, a large television; a few never-read novels, ceramic figures and other useless items scattered on a wall unit; women’s magazines spread on the coffee table. The furniture was cheap-looking, but with three kids and only one person working, they were probably doing the best they could.

Mrs Darcy, whose first name I had never asked, invited me for some lunch. I politely declined, feeling like an intruder invading a family weekend.

Instead, I followed John down a dark hallway and into his study.

His study looked like a miniature little laboratory. On one side of the room, he had his own lab bench, complete with water and gas taps, microscopes, beakers, burettes and pipettes. It looked as if I had stepped inside a VFSC-4-KIDS made with IKEA-assemble-it-yourself furniture. He confessed that he bought most of the laboratory equipment from the Mebourne Trading Post, a classifieds-only newspaper, or from auctions.

Next to his desk was an amazing collection of forensic and biology books from the USA, which I gathered would have cost him a fortune with the exchange rate and freight cost added. Some of the titles, Inside the Crime Lab and Crime and Science: the New Frontier in Criminology, amongst others, were familiar to me, except that my copies were usually borrowed from university libraries.

‘So, what have you got?’ he asked, shifting comfortably into a gas-lift height adjustable chair, finished in a paprika synthetic cloth.

He loved giving his opinion, because, like everyone else I knew, he loved to believe he was important to this world.

And he was.

I briefed him quickly on the Jeremy Wilson’s homicide.

Like ninety-five percent of Melburnians, he read the case coverage in the Herald-Sun and the Age. And since journalists could only write up what they were given, the Wilson’s coverage was rather disjointed and incomplete, not to mention poor in forensic details. Only when the case would be fully closed, the media would be able to release a more accurate version of events. As a result, some journalist, thirsty for fame and recognition, would win an impressive award for writing up something based on other people’s misery.

I pulled two postcard-sized, coloured photographs from the manilla folder I had brought with me. The shots were close-ups of blood droplets from Jeremy Wilson’s body. The blood samples had already been analysed, compared with a blood sample taken from Jeremy’s body, and confirmed to be his blood. Not that anyone had doubts in the first place, but if evidence had to be presented in a court of law in any homicidal case, the VFSC not only had to present the evidence as exhibits, but also prove its source and location.

‘Take a look at those,’ I said, as I handed over the photographs to John.

He looked at them rather quickly and commented, ‘These are drops of blood. I gather they’re from the victim.’

‘That’s right. But what else do you see in them?’

I knew what I was getting at, but I couldn’t believe how anyone could have missed something so obvious. Blood droplets were good indicators of past events at a crime scene. And yet, caught up in the horror of Jeremy Wilson’s decapitation, no one bothered examining the pattern of those droplets.

John rubbed his chin and said, ‘These drops come from a static source about two or three feet high.’ He pointed to the shape of the drops. ‘You can tell by the neat circles.’ All the drops captured by the film were starburst in shape, but perfectly circular.

‘Okay,’ I said, ‘that’s what I observed when I looked at them this morning. But what if the source wasn’t static? Would you get splashes and spurts?’

‘Certainly. Splashes tend to be common when a bludgeoning instrument is swung. Droplets of blood hit the floor or wall at an angle, clearly indicating the direction they’ve travelled from. They look like exclamation marks. Spurts are more common when a major vein or artery is severed. A forceful outflow of blood is sprayed around the victim, and, more often than not, onto the killer.’

Hell! I knew I had been right.

‘So the guy who got his head cut off,’ I asked, ‘couldn’t have been hacked to death?’

He looked at the photographs once more and back at me. ‘Absolutely not. Impossible.’

‘How would you describe the decapitation?’

‘Based on these pictures, the head has been cut slowly from the body. This was performed methodically.’

I felt a pain at the back of my skull. I wasn’t sure if it was still the effect of the Southern Comfort, or what John had just told me.

I nodded for John to go on.

‘So, what are you getting at?’ he asked.

‘Something really bothers me here.’ I removed a typed report from the Jeremy Wilson file. ‘Listen to this.’ I scanned the report. ‘According to this, Teresa Wilson, the wife of the guy who got his head cut off, said her husband was hacked to death. But according to those drops of blood, he wasn’t.’

He gave me a blank look.

I went on, ‘Something doesn’t match.’

‘Maybe she got confused. Wrong choice of words, I don’t know.’

‘This still puts the entire case under a new perspective.’

‘I don’t see how.’

‘Well, if he wasn’t hacked to death, how the hell did the killer cut his head off methodically? Did Jeremy Wilson just sit there and say, “Okay, here we go now, a bit more to the left, yes, it’s going in, I can feel it.” Surely, he would have been fighting for his life!’

John puzzled over my analysis. ‘You know, you’ve got a good point. But still, this doesn’t mean Jeremy Wilson’s wife lied.’

‘I’m not saying she did. In fact, I don’t think she lied. I want to know why Jeremy Wilson didn’t put up a fight.’

‘Maybe he got knocked out before he was decapitated.’

‘I thought about that, but I’ve never recorded any wounds or bruises anywhere

on his head during the initial observation at the crime-scene.’ I passed him my typed report, pointing out the section which described the condition of the body when I found it.

He glanced at the report and then stood up from his chair. ‘What does it matter, anyway? You’ve caught the killer, didn’t you?’

John was right, but I hated to leave loose ends.

‘You know what I’m like,’ I said, ‘if something bothers me, I won’t let it rest, or it’s going to annoy me for years to come.’

He circled the desk and moved towards the laboratory bench. He began fiddling with his compound microscope ‘You’re overworked, Melina. Why don’t you take it easy for a few days.’ He turned to me, smiled and went on,’ And if you don’t mind me saying, you look awful. Did you have a late night or something?’

‘I’ll tell you about it some other day. I could do with a cup of coffee, though. Lukewarm if you don’t mind.’

We walked to the kitchen where he made a strong sugarless black coffee in a mug. ‘I think you’re going over your head with this one,’ he said while helping himself to a glass of lemonade.

‘I know, maybe you’re right. Sorry if I’d disturbed you.’ I drank my coffee in one go, hoping it would help me stay alert for the rest of the day.

‘Hey, don’t be like that. I admire what you do. I’d be interested to find out what else you come up with. You know I’m only a phone call away. Just trust that instinct of yours. It’s all you’ve got.’

John was one of the finest people I knew.

I said goodbye to his wife and kids and apologised for the intrusion of privacy.

John walked me to the door. ‘And don’t worry about what people think about you,’ he added, ‘You’re perfect as you are.’

His comment really helped, because right now I felt as imperfect as humanly possible.

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim