- Home

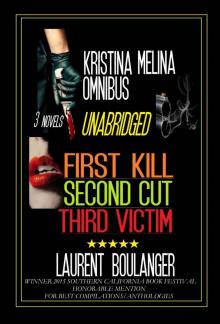

- Laurent Boulanger

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 19

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 19

On television they showed you these cops who poked at bodies, faced crime after crime, got beaten to a pulp, and yet, by the next episode, recovered as if they’d begun the life of a Born Again Christian.

But in reality, humans were far more sensitive. Television never showed the weeks of numbness, sitting at home, knees clutched to the chest, suicidal thoughts drifting in and out of one’s mind, the urgency of wanting to call Lifeline, just in case you lose the strength to carry on for one more day. Were we born to take so much violence in our daily lives? How much longer would it take before all the minds in the world would give up and lay to rest?

I removed a pair of Ansell disposable surgical gloves from my sports jacket and slipped them on. I must have looked like a dental technician who was about to perform backyard surgery.

Two steps forward, one step back.

Get a grip on yourself.

Reluctantly, but in a professional manner, I closed in on the black garbage bag.

I kept telling myself this was only part of the job, nothing more, nothing less.

Unwillingly, I undid the white plastic nylon strap that was keeping the bag secure.

The pungent odour coming from the inside of the bag was a mixture of rotten meat, urine, and methane-like-gases, all mixed into one. Not a single word could describe the horrible smell.

I pulled my head back and creased my brow.

The mug of black coffee I swallowed ten minutes ago felt like a hot iron in my stomach.

The odour filled my lungs as I wiped my forehead with the back of my sleeve.

Inside the bag was the body of a woman dressed in what was once a short floral dress. She was badly decomposed, and it was impossible to identify her by looking at her face. It had been heavily eaten by insects and maggots, and was now covered in blisters and puss.

I pushed her head back as something unusual caught my attention.

Her eyes had been pierced with yellow corn-cob skewers, and her mouth was packed with cotton wool.

Grey clouds hovered over Melbourne on Wednesday the 12th of March.

At 8.34 a.m., I was sitting at the kitchen table of my apartment, a mug of black coffee by my side. Michael had already left for school. While sipping my coffee, I scrutinized polaroids of Claire Kendall I’d taken the previous day.

I had never seen anything like it in my life. Claire hadn’t just been killed, but mutilated. This was more than a crime of passion. I smelled revenge and hatred coming from a dark and murky corner of someone’s soul.

The mutilation of the eyes with corn-cob skewers told me the killer might have felt remorseful, as if he hated the thought of Claire watching him even when she was dead. And the cotton wool packed in her mouth could mean one of two things. He suffocated her, or he wanted her to remain quiet about his identity, even after he killed her.

I was having trouble picturing Teresa Wilson being the killer, and that was probably why I imagined the killer to be male. But at this stage, evidence pointed to her, even though my instinct told me it was far more complicated than that. I hated to dismiss the idea that someone else was involved in these murders.

I had to plan my next move carefully.

I took another sip from my mug, feeling a sharp pain at the back of my cranium. I’d been sleepless most of the night, kept awake by the ghost of Claire Kendall.

When I left the Wilson’s garage the previous day, I ordered Lionel Payne to lock up and call the police. No one had to know I found the body. Just tell them you smelled something, so you went to check it out. He agreed without knowing why, probably because he thought it exciting to be a participant in one of this state’s most horrific stream of homicides.

I got home almost hysterical, looking over my shoulder, checking that the door and all the windows of my apartment were properly locked.

I was surprised Frank never called me when the police found Clare Kendall’s body. Surely, he would have seen it since the Herald-Sun took delight in running the story on the front page of this morning’s edition. For a while, I feared he might be dead as well.

For the next few days, I decided to lay low. I feared anyone connecting me with the finding of Claire Kendall’s body. I also had to get over my post-traumatic stage if I wanted to think clearly. But unfortunately, time was a luxury I couldn’t afford. I was thinking of seeing a counsellor after all, just to help me get over this difficult moment. I’d pay cash and would refuse to give the counsellor my name. I had a name and number with me from a friend who had been happy with the treatment she’d received. His name was Dr Melina Freemann, and he was a qualified clinical psychiatrist.

Straight after lunch, I went to see my contact at the telephone company, Mr Trevor Wood. He listened while curling one end of his dark moustache around his forefinger. He was reasonably good looking, broad shoulders, a straight nose and strong chin, but a bit too nerdy for my taste. Maybe it was the way he insisted on parting his dark hair to one side with a truckload of gel.

We were sitting in his partitioned office, listening to everybody else’s bit of conversation, while I explained my plan on how to catch the coin thief.

He loved the idea, and said he would get some technicians to work on it straight away.

‘Who do I give this to?’ I said, waving my invoice in front of his face. ‘I was going to post it, but since I came by, I thought I might as well drop it in.’

‘I’ll take care of it,’ he said, a broad smile on his face, as if he was doing me a huge favour.

I stood from my chair and shook his hand firmly.

He seemed to be checking out my fingers.

‘Dr Melina,’ he finally said. ‘You wouldn’t be free by any chance?’

I gave him an inquisitive stare.

The colour on his face changed to deep red. ‘I don’t mean to be rude,’ he added. ‘It’s just that, you know, you’re quite attractive. Maybe dinner next week.’

I thought about it for two seconds and said, ‘Okay, give me a call.’

He had a great body, and I could always talk him out of the hair gel.

Late afternoon, I called in at Frank’s home. My mind was all over the place. I knew I would never be able to see the light of day if Frank got killed.

I pulled into his driveway and hoped to God she was away. It would have been easier to ring first from my mobile, but I was scared she would answer the call. The worst would have been if he told her everything I told him.

He lived in Richmond, in a Victorian terrace, one of those long, narrow houses built at the beginning of the century. Its selling price was at least three times more than a house five times its size in an outer Melbourne suburb like Sunshine or Noble Park.

I rang the door bell and waited half a minute, staring at the dark green coat of paint on the front door. My stomach churned as I wondered who was going to answer it.

Footsteps came down the hallway.

Crisis time.

My hands were shaking, as I anticipated the worst.

Through the yellow, glass panel to my right, I recognised Frank’s silhouette. A great sense of relief enveloped me when he pulled the door open.

‘Melina,’ he said, sounding almost apologetic, ‘I was meant to call you. I’ve been flat out.’ He didn’t look as worn-out as I had expected. I noticed his freshly-trimmed moustache. He wore sand-coloured Haggar pants with a blue, oversized Country Road shirt. She’d already changed the way he dressed, and as much as I hated to admit it, it was a definite improvement. An aftershave I failed to recognised whisked past me.

I glanced over his shoulder and said, ‘Is she in?’

He opened the door fully to invite me in. ‘She’s at the hospital for a check-up. I’m not expecting her until seven.’

I checked my watch: 5.02 p.m.

Plenty of time.

I followed him into the narrow, dark hallway, wondering why he was being so friendly and courteous.

‘Have you heard?’ I asked.

‘Of course I’ve hear

d. Doesn’t mean anything.’

I was staring at the back of his neck when he said that.

We went straight to the kitchen, where Frank filled two glasses with ice and water, not asking if I wanted one.

Dishes were piled up in the sink. The Age newspaper was wide open on the table, and an odour of dampness circled the room. Cleaning was obviously not one of their favourite pass times.

He sat at the wooden table opposite me with both drinks. He pushed one glass in my direction.

I tried to make eye contact, but he kept his head lowered, stirring the ice cubes in his glass with his forefinger. ‘I’m sorry, Melina,’ he finally muttered, tilting his head forward, ‘but I don’t know how to handle this.’

I was unsure what he was getting at. ‘What’s wrong? You need to tell me something?’

He looked up. His eyes were red as if he was about to cry. ‘I was called up at work yesterday. The Deputy Commissioner of Police was there with two detectives from the CIB, and they started probing and asking questions. This was straight after they found the body of Claire Kendall. They wanted some answers. We talked for a while, and a decision had to be made. They gave me no choice.’

I felt nauseous. ‘What Frank? You had no choice about what?’

‘Your contract with the VFSC and the CIB has been terminated as of yesterday.’

I felt a lump in my throat. His words cut through my mind like a giant circular saw. ‘Jesus, what did you tell them?’

‘I explained how you were trying to help, all you wanted to do was find out the truth, but they wouldn’t have a bar of it. They said you were only on probation. This was only an experiment, you know, having someone working as an investigator as well as a crime-scene examiner. Well, they thought it wasn’t working.’

It took me a full thirty seconds for the news to sink in.

I could tell from the look on his face he expected an outburst.

Finally, I shifted on my chair and snapped. ‘Why wasn’t I called in? No one spoke to me. I could have explained everything. I could have at least defended myself. When they made me sign the damn contract, everyone was being friendly and courteous, as if they had just crowned me Queen of England. What the hell happened in there? Did you really try, Frank, or was it convenient for you to get rid of me?’

He pursed his lips as I wondered why I was taking it so badly since I knew I was going to lose my job eventually. It would only have been a matter of time before the axe fell on my head. But I took it badly. I could live with losing my job, but not the way I lost it. No hearing, no chance to explain myself. At this stage I was considering taking them to court for unfair dismissal.

A heated rage built up inside me. Even though lately things had been patchy between us, I believed Frank was my friend. I thought he would have fought like only a friend could to save my job. If our roles had been reversed, I would have done my utmost to make sure he kept his job.

I shook my head in disbelief.

He could have insisted on having me there. They could have never got rid of both of us in one go. No one out there could jump into both our seats, not immediately anyway.

‘Fuck you, Frank,’ I went on. ‘I risked my neck for you. I’m doing this because I’m scared I’m going to find your naked body lying in bed and your head watching television.’

He glared at me strangely without a word. Motion in his cheekbones indicated grinding of teeth. ‘Everything could have worked out,’ he finally said, ‘if you didn’t probe so far. You could have told me what you were up to.’

I wondered what he was talking about. Confused, I threw him an inquisitive glance.

He continued, ‘I know you found the body of Claire Kendall before the police did. They told me.’

I felt heat on my cheek. ‘What?’ My surprise was genuine.

‘Come on, Melina, stop playing games with me. Lionel Payne told the police. I don’t think he meant to, but he’s old, and he made a slip of the tongue.’

I felt like a total fool. ‘You mean everyone knows?’

He nodded and gave me that sorry puppy look. ‘Trevor Mitchell wants you to hand over every single file on every case you’ve worked on for the VFSC. He’s going to make sure you’ve got nothing more to do with the Wilson’s homicide.’

The idea of suing for unfair dismissal suddenly seemed pointless.

He stared at me as if it was out of his hands, but we both knew that was not the case. He could still do something if he wanted to. He could appeal to a higher authority.

I was thirty-nine and had to look for a new job. Forensic investigation units were not Coles supermarkets. If I wanted to continue working in this field, I had to go interstate or overseas. Even then, my resumé was now tarnished.

I couldn’t take any more.

‘Fuck the VFSC, Frank. And fuck you.’

I stood up, sending my chair flying behind me. It crashed loudly on the tiled floor, invigorating my anger.

I raced down the hallway.

‘Hold on,’ I heard him shout as I slammed the door in his face.

The following day, back from some grocery shopping at Safeway in Acland Street, I dialled the VFSC from my mobile phone and asked to speak to John Darcy.

‘Melina, I’m sorry about your contract,’ John said as soon as he heard my voice.

‘Never mind that,’ I said, pulling into my driveway. ‘I need your help.’

He didn’t respond.

‘John?’

‘Yes, well, it’s not all that easy. You’re not working for us any more.’

‘So, you’re not going to help me?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘So, what’s the problem? They got to you too, did they?’

‘Melina, you make it sound like they’re the Mafia or something. I’m willing to help to a degree, but these people are my superiors. I’m not like you. I’ve got a family to think about. I can’t just take risks like that. If someone finds out I’m leaking information to you, I’m finished.’

I pulled the handbrake hard. ‘I get the point. Thanks for your help.’

I terminated the call and killed the engine.

The bastards were going to make it impossible for me to do anything. I had no access to VFSC facilities, no one to advise me on forensic tests, and the police were probably going to monitor my every move.

I could only see one advantage in all this.

Why should I stop investigating since I had already lost everything?

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Saturday the 15th March was sunny but the temperature was in the low twenties. I was up early, trying to come to terms with my new life as a nobody.

By 6.45 a.m., I was jogging on St Kilda Beach, alongside the Esplanade. Seagulls were hovering above my head, crying in unison. The ocean was magnificent in the morning, like a gigantic grey blanket blending in with the clouds above. A taste of sea water hung in the air, giving the illusion of being on holidays, hundreds of kilometers away from the city life, stress, and the too-often meaningless daily routine. The perfect place to clear my mind and think about my future.

Although I managed to put enough money aside, I hated the thought of living out of thin air. The last thing I needed was to drain my savings, sell my car, my apartment and my belongings one at a time, just to make ends meet. And I hated the thought of applying to Social Security. Unemployment benefits had a purpose, but were designed for people who were looking for work. I knew if I really wanted to work, I could get anything within a week. It would take more than that for my Social Security application to be processed. In addition, I’d find it unbearable to stand fortnightly in a queue and beg for a handout.

I got back home and took a long, hot shower.

My first mug of black coffee was replaced by freshly squeezed orange juice and sultana enriched cereal.

After breakfast, I slipped into comfortable jeans, a white T-shirt and a black leather jacket I bought at the South Melbourne Market for a bargain, less than a

hundred dollars.

By 9.26 a.m., I tucked under my arm a manilla folder filled with photocopies of the entire Wilson’s case, or as much as I managed to get my hands on since the beginning of this investigation.

Did they really expect me to give up so easily?

Finding a parking space in front of St Patrick’s Hospital was hell as usual. The spaces reserved for medical staff only were filled, leaving me at the mercy of the streets like the rest of the world. Even though I loved driving my car, I seriously considered getting a motorcycle for those days when I couldn’t be bothered with the traffic or fighting over the last remaining parking space in Melbourne.

I ended up parking around the corner from Barry Street and walking back to the hospital, hiding my eyes behind a pair of Ray Bans.

As I climbed the stairs of St Patrick’s Hospital on my way to see Dr Larousse, I hoped no one had got to him yet. I still had the basic right to talk to anyone I wanted. After all, he wasn’t a detective, nor a VFSC employee.

The previous day, I’d returned the original documents from the Wilson’s case, and every other case I worked on, to the VFSC. Before hand, I photocopied every single page, graph and photograph from every file and locked them in the first two drawers of my filing cabinet at home. I knew this would be a temporary arrangement. Someone might decide to get a warrant and search my place if they thought I’d kept documents which I had no right to. Eventually, I’d transfer every document to a CD and store it in the middle of my classical music collection. It would be a day’s work, but worth every minute. I might even leave a copy at a friend’s place, just in case someone stole my three-hundred and twenty-eight compact discs.

I took the original documents to the VFSC in person. I didn’t want to see Trevor Mitchell or anyone. I left two cardboard boxes filled with confidential material at the reception. When the receptionist said the director wanted to see me, I bluntly retorted, ‘Well, I don’t want to see him.’

Dr Larousse welcomed me in his office. He assured me no one from the police spoke to him and seemed genuinely disappointed my contract with the VFSC had been terminated.

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim