- Home

- Laurent Boulanger

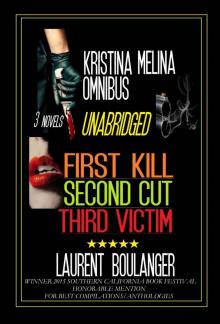

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 3

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 3

I began pushing my way towards the apartment.

‘How did the victim die?’ The journalist went on. ‘You didn’t tell us how he was murdered.’

‘Decapitated,’ I answered dryly and entered the building.

Frank Moore and I spent the next five hours going over the Port Melbourne apartment, where the murder of Jeremy Wilson and the battering of his wife Teresa took place. One of their neighbours had informed us of their identities.

We called the State Emergency Services (SES) to provide us with adequate lighting of the area, inside and out of the building.

Prior to collecting evidence, we proceeded with a preliminary examination, which entailed observation only. The last thing we needed was to risk contaminating the crime scene any more than we already had. Collection of evidence would be done after we’d made a thorough assessment of the crime scene.

The preliminary examination was a walk-through evaluation of the crime scene. This stage was one of the most critical phases of searching the crime scene for evidence. The impressions we gained from this walk-through were going to formulate how the scene would be processed.

During the walk-through, Frank and I kept our hands deep inside the pockets of our overalls, just to stop ourselves from touching anything.

We moved through the apartment by walking in areas which did not appear to contain any potential evidence. I took extra care when walking through the hallway, doorways or any areas where potential footprint or footwear impressions, fingerprints, and other trace evidence could have been left behind.

The only rooms which seemed to have been disturbed were the bedroom and the hallway. A small window in a room adjacent to the bathroom had been left ajar.

I made mental notes of any sign of forced entry, the location of potential items of evidence, and the presence or absence of blood in various areas of the scene.

Following the preliminary examination, we videotaped the entire area.

Since the introduction of the video camera nearly two decades ago, forensic investigators had additional means to accurately record information. This method of recording information at a crime scene was better than photography at times, because it gave us a three-dimensional view of our surroundings. It also provided us or anyone working on the investigation with a powerful tool to help re-construct a chain of events. Videotaping was also being introduced more and more in courts of law, making a strong visual impact on the jury. This proved very effective when shock and disgust was the reaction the prosecution was aiming at.

We divided other tasks to avoid stepping on each others’ toes and to minimise risk of contamination of the exhibits collected. At no time should two pieces of evidence come into contact with one another.

Frank was outside taking the overall and mid-range photographs of the location, including the street sign with the name clearly identified, the front the apartment, and close-ups of any points of interest. Later, if this homicide ever ended up in court, we would have to prove not only how we collected the exhibits, but also where we collected them from.

I took the initial photographs of the immediate crime scene. This had to be done before the removal of Mr Wilson’s body. I recalled that pictures of Mrs Wilson should have been taken before she was sent to hospital, but in the condition we found her, I felt at the time photographing her could wait.

I circled Mr Wilson’s body and took as many pictures as humanly possible, including close-ups of all visible wounds, bruises, cuts, hands and fingernails. More shots would be taken at the mortuary. For every photograph taken, I used an identifying scale or ruler whenever possible, and made appropriate notes whenever I deemed it necessary.

I noticed that the open wound above the chest where Mr Wilson’s head had been severed had stabilised. Although the body was drenched in a pool of blood, making it very difficult to take photographs without causing a mess, little blood was now running from the neck wound. I took shots at various angles and under different light conditions with the help of a portable flash.

I then proceeded with the photography of the entire bedroom.

Photography was vital for the recording of the crime scene in its original state.

I took hundreds of shots, including detailed photographs of foot marks, blood stains, tool marks, or anything I felt would help with the investigation and, ultimately, the jury in a trial. Nothing could be touched until photography had been completed. Later I would be able to collect exhibits, knowing exactly where I collected them from with the help of photography and painstaking note taking.

Half way through my task, I felt light-headed. I looked around me. Everything seemed surreal, like a still from a horror movie. My tongue was dry like a piece of cardboard. I needed a drink, but knew I shouldn’t use any utilities in the apartment. I swallowed and went on with my task.

In addition to photography, I recorded the scene with a sketch. Photographs were two dimensional, and only sketching would give a more accurate idea of measurements. I began with the rough crime scene sketch as soon as I removed and stored the last roll from my Minolta.

I did the sketch on a blank pad. Not exactly a work of art, but it contained enough information which would allow me to work on a final sketch with the help of Sirchie Fingerprint Labs, a computer program designed to accurately create a final sketch from the rough sketch made at a crime scene. The software included crime-scene template libraries with a variety of computer clip-art images, such as positions of victims, weapons, furnishings and bloodstains.

The scene sketch provided me with accurate spatial relationships of every item within the scene. I wrote down every essential piece of information, including the case number, descriptions, the date and time, measurements and scale, and a compass (north) indicator.

One hour into the crime scene evaluation, the coroner arrived. Since I had already finished with the photography, Mr Wilson’s body was ready to be removed from the scene. The coroner placed protective paper bags over Mr Wilson’s hands prior to carrying the body into the mortuary’s van. This procedure protected evidence which might have been present under the fingernails and would be collected later at the mortuary.

The coroner evaluated wounds, post mortem interval, and whatever indicators could have suggested the body may have been moved.

He then proceeded with the help of an assistant to whisk the body away to the mortuary.

I finished my sketch and sighed. Here I was in the middle of the night, bathing in a blood bath, collecting relics from the dead. How did my life turn out so intriguingly complicated?

I proceeded with the collection of major evidence items. This required a great deal of care since any items could have contained trace evidence and fingerprints. Most items were packaged in paper rather than plastic to avoid mould growth from a wet or moist exhibit. I took down details of any stains or damage observed on every item. When packaging was completed, I attached an appropriate label which identified the case number, the item number and a brief description of what the item was.

The collecting of trace evidence would need more time and care. Nothing could be rushed when collecting and recording information at a crime scene. This proved next to impossible since everyone who felt they had some kind of jurisdiction at a crime scene wanted everything done perfectly yesterday.

Trace evidence was the cornerstone of forensic science. Such evidence was normally invisible to the naked eye and included hair, fibres and paint particles. When collecting trace evidence I always kept at the back of my mind a famous observation by Dr Edmond Locard, the father of forensic science: The microscopic dusts which cover our clothes and our bodies are silent, yet certain and reliable witnesses of each of our actions and contacts.

I proceeded with adhesive lifts and vacuum-sweepings of areas of particular interest, especially those which were covered in dust, fibres and other foreign objects. I took great care while collecting vacuum sweepings. I made sure the vacuumed areas were specific, not a general "house cleaning" of the

crime scene. I’d been made aware a thousand times by laboratory personnel at the VFSC that a large container of dust, hair and fibre was extremely difficult and time consuming to sift through. The last thing I needed was to be known as the monster who gave them boxes filled with common household dust.

Hair and fibres were a pain to collect. Vacuuming or tape-lifting was out of the question since it may have damaged the tiny exhibits before examination.

Blood stains on clothes were collected by using clean scissors and placing the item into a piece of folded paper and then into a labelled plastic-bag. Blood stains on the ground or furniture were scraped using a clean scalpel, or sponged up with a wet piece of cloth, and also stored in paper and plastic-bags.

I’d nearly finished collecting most of the trace evidence in the bedroom when Frank walked in. I was kneeling down with a scalpel in one hand and a folded paper in the other.

‘Found some interesting stuff,’ he announced while looking at his notepad.

I twisted my lips and looked up. He knew he shouldn’t have been in the room at the same time as me, but I let him speak before telling him off.

‘You remember the back window?’

‘Which one?’

‘The one in the room adjacent to the bathroom.’

I nodded. When we did the preliminary examination, I’d made a mental note of the open window and wondered if it was the point of exit.

Frank lifted a labelled transparent vinyl bag and went on, ‘A piece of dark fabric got caught in the rotted outer woodwork of the window frame. Looks like the fucker escaped through the back.’

Frank had just confirmed the point of exit.

I raised my eyebrows for him to go on.

‘The front door’s been forced from the outside by what looks like some kind of leverage tool. Definitely the point of entry.’

I had already noticed that when we first entered the apartment, and when we did the walk-through.

Frank took a deep breath and continued, ‘And now for the mother of all evidence.’ He opened a Postpack. ‘A cook’s knife with a twelve-inch blade covered in blood. Found it in the back alley.’

Okay, I had to admit, things were starting to look good. ‘I want this whole damn place fingerprinted as soon as I finish with the collection of evidence. Call the fingerprinting unit when we’re done,’ I said with excitement. ‘We’re gonna nail the sucker who did this. He’s such an amateur, he’s left a trail of evidence all over the place.’

I took the Postpack from Frank’s hands, and examined the cook’s knife up-close. It was covered in blood, but I could still read the serial number on the handle, G-66923. Although Frank had already done that, I wrote the number down in my log book. I liked to keep a record of vital exhibits for myself.

‘Hey, I’ve already recorded the details,’ Frank protested. His face was flushed.

‘I know, I know.’

‘So what are you doing?’

‘Just go and finish what you’re doing.’

‘We’re supposed to keep separate logs. You’re gonna get us confused.’

‘We’re also supposed to keep investigating in separate rooms to avoid contamination of evidence. Now, go and finish what you’re doing.’

‘Jesus,’ he muttered and walked off.

I removed a small stainless steel ruler from my right pocket and measured the length and width of the knife. A large 30 x 3cm piece. I wrote down the information and took a photo. This precaution was vital in case the knife went missing in the future due to mishandling of forensic evidence by one of the many people who were not authorised to touch evidence, but who would anyway. I filled in my name on the label attached to the Postpack to preserve continuity.

Just as I placed the knife back in the Postpack, Frank walked back in the room.

‘I thought I told you not to come here,’ I snapped.

‘The Deputy Commissioners just arrived,’ he said in a tone that meant trouble.

The Deputy Commissioner of Police was a short, fat guy by the name of Frank Goosh. I never figured out how the hell he ended up with a name like Goosh. It sounded like something out a comic book.

Frank Goosh couldn’t stand the sight of me, and I cared little for his opinion. Right from the beginning, he had opposed any restructuring which involved the contracting of civilians to conduct forensic and investigative work. And although he never admitted it openly, I knew he had a hard time accepting that the first person who had been contracted as an unsworn crime-scene examiner and investigator happened to be a woman.

I stood on my feet, my body fully erect. ‘Where is he now?’ I asked, feeling blood rushing to my head.

‘He’s just outside the front door. Just about to walk in here’ Frank said.

‘Jesus Christ!’

I stormed out of the bedroom and down the hallway. My duty as crime-scene examiner was to insure no one entered the crime scene, not even the Prime Minister or the Queen of England. The Deputy Commissioner of Police was well aware of that, but for some reason he obviously believed himself to be an exception.

I intercepted Frank Goosh in front of the apartment, inside the perimeter of the crime-scene, which Constable Gus Patterson had so obediently sealed off with blue and white police tape.

The Deputy Commissioner of Police came towards me, his pot-belly almost bursting out of his blue shirt. His black hair was parted in the middle, his beady dark eyes had virtually no white in them, and his complexion looked like raw hamburger.

‘Have you got the situation under control?’ he inquired in a tone which reminded me of my school principal a long time ago.

‘Mr Goosh, glad you could make it, but I don’t recall requesting your presence at this crime scene. Now, if you care to step outside the crime-scene perimeter and stand behind the police tape like everyone else, I’d very much appreciate it.’

‘I’m the Deputy Commissioner of Police, Miss Melina. I have a right to be here.’

‘It’s Dr Melina. I’ve earned a degree in criminal justice through diligent and hard work, and would appreciate if you would address me as Dr Melina.’

He shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other. ‘Dr Melina, you’re only here because of me. I can have your contract terminated anytime.’

‘I appreciate your need to exert your power, Mr Goosh, but right now you’re going to step on the other side of the police line.’

He crossed his arms over his chest, making his stomach protrude even further. ‘And who says? You’re going to make me? What the hell is your problem, anyway?’

‘Mr Goosh, I have legal jurisdiction over this crime scene. If you can’t understand that, maybe you should consult the Police Operations Manual and familiarise yourself with its content. In the meantime, either you step on the other side of the police tape, or I’ll have you escorted by force.’

He gave me a cold stare. ‘Bitch!’

I moved two steps forward. ‘What did you call me?’

‘You heard. You think you can just walk in and take over everything. I’ve been doing this longer than you have. I have years of experience. You were still sucking on your mother’s nipples when I was chasing criminals. So don’t lecture me on what I can or cannot do.’

I felt like running my scalpel right across his throat.

‘Mr Goosh, I’m not going to ask you again.’

‘You don’t know who you’re dealing with.—’

I interrupted him before he had time to insult me once more. ‘Constable Patterson,’ I shouted towards the young officer, who was standing close to the Channel 10 news crew, ‘Could you please escort Mr Goosh out of the crime scene?’

‘Yes, Dr Melina,’ Constable Patterson said, already pacing towards me.

Frank Goosh glanced over his shoulder, towards the constable and turned back at me. ‘I’m going to get you for this. You can kiss your job goodbye, you little tart.’

He walked off before Constable Patterson got to him.

I stepped back in th

e hallway, feeling myself shaking all over.

Goddamn sonofabitch managed to get me frustrated.

I clenched my teeth and proceded with my task.

By the time we closed the place up, we had collected clumps of hair, slivers of broken fingernails from the most unreachable places, a multitude of various fibres, and enough fingerprints to jail the killer twenty times over.

The beheaded body of Jeremy Wilson was now resting in peace somewhere at the mortuary in Southgate, for a little while anyway, until an autopsy would be performed.

When I climbed back into Frank’s Ford Falcon, it was 8.21 a.m.

Daylight had set in a few hours ago. Towards the first hours of daylight, collection of evidence had become much easier. I saw fibres and marks I hadn’t been able to see at 3.00 a.m. in spite of additional lighting provided by the SES. I hated collecting evidence at night time, and usually I would wait until the next day. But since we knew we had a killer on the run, we didn’t want to waste any more time than necessary.

Frank took a turn into Princes Highway, where the traffic moving towards the city was becoming rather congested. Another working day for normal people.

Drivers were aggressive, as if they actually wanted to get to work more than anything else in the world. Had it been me, I would have taken my time.

Passing one hand over the length of my oval face, I sighed. I was tired and angry. Tired from not getting the sleep I deserved, and damn angry men could commit such atrocities as the one I had seen at the Wilson’s place. Over ninety percent of violent crimes were committed by men. Whoever had masterminded this little set-up had the brain of a monkey.

I tightened my seat-belt and turned to Frank. ‘Men are a real hazard to the community. This world is in the shape it’s in because of men. Without them, there’d be virtually no crime in society. Imagine that, a world without crime.

He shifted uncomfortably.

I made my hands into fists and went on, ‘I read once that men should pay extra tax just because they’re wasting tax payers’ money.’

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim