- Home

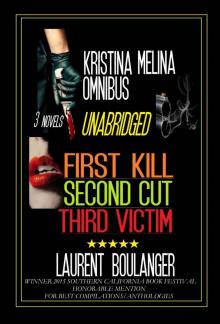

- Laurent Boulanger

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 26

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 26

While I was seated in the front row, sandwiched between Frank and Dr Main, the entrance door to my left opened, and in walked a forty-something woman with a face of stone. I guessed this had to be the little girl’s mother. She seemed upset, but her grey eyes gave no indication she’d been crying. I guessed her to be around eighty kilos and one-seventy in height. She wore a budget-type, ankle-length white summer dress with a pair of brown, leather sandals. Her brown hair fell over her forehead and was tied into a pony-tail. Her nose was short and round, and her lips chunky and painted dark red. She avoided eye contact, giving no indication that she noticed our presence in the room.

We waited patiently in embarrassing silence while someone wheeled the dead girl’s body on a galvanised mobile cart from the cool room, down a maze of corridors and into the viewing room.

Finally, the assistant pathologist pulled open the green curtains to the viewing room.

Laying on the galvanised mobile cart, the young girl, whom I’d seen this morning at Albert Park, was covered in mud, but her face was still identifiable. I recognised the blue dress we found her in. She wore a toe tag, filled with an accession number and identification, which still remained to be confirmed by her mother. The girl had been reported missing the previous night, and the description Mrs Noland had given the police matched the body we’d found this morning.

Frank whispered something to her, which I didn’t hear, but assumed had to do with the identity of the young girl.

‘Yes, it’s her’. Her tone was surprisingly deadpan.

My heart sank so low that I felt as if I was going to pass out. How in the world did I end up in a room with a bunch of strangers, staring at the white corpse of an eleven-year old girl?

The mother of the young girl seemed emotionless, but maybe she was only experiencing some form of time-delay reaction. I’d seen people who’d refused to accept the death of a loved one for days, sometimes weeks after it occurred. I’d heard of some who still wouldn’t accept the cold, hard truth years after the person died.

The grieving process was a strange one, sometimes a never-ending phase where people left behind hung on to the hope that their loved one would come back one day. When someone got killed, the victims were multiple, ranging from brothers, sisters, parents, other family members and friends, all suffering from varying levels of grief.

And then there was the temporary presence of strangers like me, who could never quite distance themselves emotionally from the curse which had inflicted other human beings.

When we left the viewing room, churning emotions challenged my choice of career. Why was it that I had a morbid fascination with other people’s misery? I liked to believe it was compassion which drove me to the job I was doing, but as time went by, I wondered if that wasn’t just an excuse to avoid facing the real reason behind my unhealthy interest. Was there a dark side to me which I refused to face? Deep down, did I enjoy the grieving pain I experienced every time someone died?

Down the hallway, which was covered in a dark blue carpet, just past the reception area, the girl’s mother stood like a marble statue, while Frank and a uniformed officer were chatting. I stared at her for a few seconds, wondering what was going through her mind. I thought about my son Michael and tried to imagine how I’d react if the same thing had happened to him. He was the only person who truly mattered in my life, the only reason I managed to wake up everything morning and find the strength to carry on in a world that had gone mad.

I tried to sneak out of the building, determined not to get more involved than I already was. Soon, this case will be behind me, handed over to someone else, and I would get on with life as if this whole incident had been nothing but a bad dream.

But before I made it past the reception desk and out the side door, Frank spotted me and said, ‘Hold on a sec, Kristina.’ Then he turned to Mrs Noland and muttered something I didn’t catch.

She turned to me, her eyes cold and empty.

Obliged, I paced towards her. God damn, why can’t they just leave me alone?

‘I’m so sorry about Tracy,’ I said, injecting my tone with sincerity. ‘The police will do the best they can to find the person responsible.’

She forced a smile and said, ‘I understand you’re investigating the death of my daughter?’

I gave Frank a cold stare, but in return he shrugged as if to say what the hell did you want me to say?

‘That is correct,’ I said dryly. ‘But someone else will take over the investigation. I’m only working temporarily on this case.’

‘You find the killer, Dr Melina,’ she commanded, obviously not registering what I’d just said. ‘I’m never going to sleep again for as long as I know this person is still out there.’

There was bitterness and anger in her tone which was hard to ignore.

I swallowed hard and was about to protest when she went on, ‘I know you’ve got a child of your own. As one mother to another, please do your best to find the killer.’

And then she let a tear roll down her face.

The first tear since she walked into the mortuary.

Oh, God!

I couldn’t help myself.

I took her hand in mine and said, ‘I will, Mrs Noland. I’ll do the best I can. I promise.’

After Mrs Noland had gone, I gathered my notes and went to lunch with Frank in the VFIM’s staff canteen. A few people were scattered at various tables, talking in low voices as if they were afraid to wake the dead.

I was trying to get some information on what Goosh had said after I left the St Kilda Road Police Complex this morning.

‘So he said nothing else?’ I asked, pulling the ring from my Diet Dr Pepper.

‘All he said was that the police needed a real expert, and despite your qualifications, he didn’t think you were a real expert.’

‘And what did you say?’

‘Nothing. What was I supposed to say?’

‘You said nothing?’

‘Kristina...’

I made a throaty noise and sipped from my Dr Pepper. ‘Well, you can tell that sonofabitch that I’ve decided to stay on the case. Changed my mind.’

Frank locked his eyes into mine, his way of asking if I was serious.

I nodded.

A smiled appeared on his face, and he said, ‘This is great, Kristina. I was hoping you would re-consider. Well, I’m sure Goosh will be delighted to hear that.’ He placed his right hand on his mobile phone, which was laying next to his coffee cup. ‘Do you want me to tell him the good news now?’

We both laughed loud enough for the other people in the room to stare at us.

‘Ah, almost forgot,’ Frank said between laughs. ‘Some neighbour of the young girl called the station. He said he wanted to talk to someone about the murder.’

My face straightened.

‘Did you get a name?’

‘Not me. I wasn’t the one who took the call.’

I scribbled something in my notebook about chasing up this lead.

I finished my cheese-and-salad sandwich and knew it was time to face reality.

I hate autopsies, and they’re not something I would wish on anyone. In fact, as I was waiting in the homicide room for Dr Main to make an appearance, I told myself that when I’d die, I’d make sure it would be a straight-forward death. Only people who died under suspicious circumstances or old age ended up at the mortuary. I knew what they did at the mortuary with the dead. Although the autopsy consisted of straight-forward clinical procedures carried out with the greatest respect for those whose souls were floating above the room, no matter how many autopsies I attended, I couldn’t help feeling nauseous about the entire procedure.

Attached to the homicide room was a viewing room, where Frank and a police photographer were sitting on high stools, ready to witness the forthcoming autopsy.

The autopsy room consisted of a blue-green concrete floor, a galvanised table with holes to allow water and fluids to drain, a small-parts dissection table w

ith drains, a vertical mechanical scale to weigh each organ, and a tank for delivering water to the table and collecting fluids. The ceiling was white with various pipes criss-crossing like spider webs. Yellow plastic bio-hazard containers were scattered in various parts of the room.

Every pathologist has personal preferences when it comes to post-mortem instruments. Dr Main had his own collection, which included dissecting and brain knives, scissors, saws of various sizes, a skull key, forceps, scalpels and chisels, all succeeding in making me shiver just by looking at them.

A strong disinfectant smell filled my lungs, as if we were in a hospital, except that unlike a hospital, anyone lying flat in this room had nil chance of ever getting up again.

Air conditioning hummed from the ceiling, making the room cold and uninviting.

I noticed a sign which read, ‘Absolutely No Smoking, No Eating, No Drinking In This Room,’ and wondered how anyone could.

Without warning, a mortuary technician rolled in a galvanised mobile cart with the body of Tracy Noland. She was still wearing a little blue floral dress, but no the black leather shoes and knee-length white socks she wore when we found her were gone.

Dr Main followed thirty seconds later. He took me to the change rooms adjoining the main mortuary laboratory, where we traded our clothes for blue hospital pyjamas, green surgical gowns, giant white rubber boots and white disposable plastic aprons. Without a word, we returned to the homicide room, where Frank and the photographer stared at us like children stare at monkeys at the zoo.

‘How are you holding up?’ Dr Main asked, glancing towards me.

I was standing in one corner of the autopsy room, next to a cork board filled with various procedural instructions, trying hard not to be a nuisance. All I wanted was the damn thing to be over and done with.

‘Great. It’s exactly what I look forward to every day after lunch.’

He laughed gently, and I couldn’t help smiling at his reaction to my own humour. But when I looked back at the mobile cart and the dead body of the eleven-year girl, I realised there was nothing to smile about.

He saw me looking at the high window strip along one of the walls, where sunlight spilled into the chilly laboratory.

‘Natural light is better when conducting an autopsy,’ he said. ‘You can see skin discolouration from carbon monoxide poisoning. Colours are more vibrant, more real than in artificial light.’

I nodded, unsure if this was a good or bad thing.

‘Okay, Dr Melina, I’m going to be recording the autopsy to help with the report. If you have any questions, you can ask me when I’m finished.’

I nodded as he slipped on a pair of yellow surgical gloves.

Mrs Noland managed to talk me into this, and now I knew there was no turning back. This investigation was another one of those moments in life which I had to go through, gritting my teeth, hoping the end would be coming soon. But as it was, I was perfectly aware that I was at the beginning of the investigation, something which made me even more upset.

I stood straight and told myself that no matter how badly I wanted to get out of this, now that I’d made the commitment to find out how and why Tracy Noland died, I was better off taking it as well as I could. Complaining wasn’t going to get me anywhere other than in a state of anger.

Dr Main began by taking photographs of the entire body clothed. When he finished, he switched on a video camera, next to the dissection table, angled in such a way that the entire autopsy would be clearly recorded.

And then, he began the examination.

‘Subject is an eleven-year old girl known as Tracy Noland. She has blond hair, blue eyes, fair complexion’. He proceeded with measurements and weighing of the body. ‘She’s one-hundred-and-forty centimetres tall and weighs forty-seven kilograms. The front of her body, including her face, and all her clothes are covered in mud. At first glance there seems to be no visible injuries of any kind.’

Tracy Noland was then undressed. Every item of clothing was carefully bagged in large yellow envelopes marked ‘PATIENTS CLOTHING’ in bold green characters. Each envelope was labelled with the item number, case number, date, time, and a small description of the item in question, all ready to be sent to the relevant departments of the VFSC.

Dr Main proceeded with the examination while I stood quietly where I’d been standing since I walked into the room.

‘Hands, fingernails are clean apart from mud.’

I noticed she had a hairless, clean public region, making me realise she hadn’t even reached puberty yet.

Dr Main examined the entire body, noting nothing unusual. ‘No wounds or bruising of any kind. The victim wasn’t sexually assaulted or beaten.’

But when he looked further, he added, ‘There is some bruising on the inside upper lip, although not on the outside. Suggested smothering at this stage.’

As Dr Main gathered his surgical instruments for the internal examination, I tried to figure out who could have killed the young girl. I knew it had to be someone who knew her, or someone who saw her routinely. I crossed out a chance attack since she hadn’t been sexually assaulted, and the most-common reason killers grabbed little girls at random is to satisfy their sadistic sexual gratification.

Did Tracy Noland witness something she wasn’t supposed to have seen? Did someone catch her in the act and decided to get rid of her just as a precaution? It was far too early to establish a modus operandi or in-depth psychological profile of the killer.

I was purposely lost in thought when Dr Main conducted the internal examination of the body. When I did pay attention to what he was doing, it was no little girl on the table, but a whole body cut open from the breastbone to the groin, her inside exposed, her vital organs lying on the dissection table.

My lunch came up to my throat for a split second.

That’s it, I can’t take any more of this.

I excused myself and left the autopsy room. Whatever Dr Main would find, I’d read it in his report.

I rushed to the women’s room down the end of the corridor, pushed the door with my right foot, headed straight for a cubicle and let the sickness out of me. Out came my salad-and-cheese sandwich with Dr Pepper. I was on my knees, my stomach contents trying to come through my nose as well as my mouth. I gasped for air, feeling pain in my chest, while holding both sides of the cubicle. I wondered if someone in heaven was having a good laugh at my expense.

When I finished, I stumbled to the hand-sink and splashed my face with cold water. My hands were still trembling. I decided that a good walk down St Kilda beach would get my mind back on track. It was only mid-week, but the way things were going, I wondered how I was going to make it past today.

On my way out of the VIFM, I told the receptionist to tell Dr Main I had left for the day, if he could be kind enough to send me a copy of Tracy Noland’s autopsy report as soon as he finished writing it up.

I slid behind the wheel of my car, confused and ashamed of myself. For someone who was supposed to be Victoria’s foremost forensic expert, I wasn’t doing too well.

I cracked the gears into reverse, did a u-turn and stepped angrily on the accelerator.

St Kilda beach was almost deserted at three o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon. With the entire beach to myself, I breathed in the soothing sea water while seagulls cried in unison above my head. I hoped to God none would have the brilliant idea of beginning target practice. The sun was high in the sky. Grey clouds peaked shyly at the horizon, and, according to this morning’s weather forecast on Radio National, would take over Melbourne before sunset. A hot wind was still blowing from the ocean, causing my skin to dry.

I walked passed an ice-cream kiosk surrounded by white plastic tables and chairs, and Coca-Cola umbrellas protecting nobody from sunburn. I almost gave in to one of those rich chocolate-coated ice-creams advertised on TV where a female model seemed to be experiencing the ultimate orgasm at first bite. But then I recalled the extra kilos I had put on since I’d stopped going t

o the gym.

I loved St Kilda, a bay-side suburb attached to Melbourne, where shops were open seven days a week, and people worried more about quality of life than climbing the corporate ladder. There was a good mixture of successful artists, bums and students, searching for an ever-lasting holiday environment without having to move all the way up to Queensland. Prostitutes and drug addicts crawled down Fitzroy and Grey Streets at night and vanished during the daytime like zombies, except on weekends when they were visible at all hours. Like every big city in the world, Melbourne had its share of homeless, burglars, junkies and prostitutes. It wasn’t a perfect world, but a perfect world would have been boring.

I strolled past Luna Park towards Acland Street, my mind filled with homicidal hypotheses.

I knew the death of Tracy Noland could have been accidental. Maybe she screamed and someone tried to quiet her down. Maybe the killer held his grip too hard for too long until she could no longer breath. Maybe he didn’t know what to do with the body once he found out she was dead. The girl hadn’t been sexually assaulted, making it even more difficult to conjure the killer’s motivation. What was it that she saw or heard to make someone desperate enough to kill her?

Because Tracy Noland had been found in Albert Park, an inner-city suburb, I concluded the killer had to be a local. No one would have taken a corpse from an outer suburb to the city and dump it there. It would have been easier to get rid of it in an outer suburb, where there were less people around and more open spaces available to dump the body without getting caught. Tracy Noland’s murder didn’t seem premeditated. And that gave me hope that the killer might have left enough clues on the way.

My next step was to conduct door to door interviews in the neighbourhood where Tracy Noland lived. From past experience, I knew that everything in life was related, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, and a murder was no different. Someone somewhere had to know something. What I had to figure out was who and where.

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim