- Home

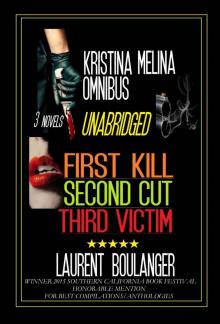

- Laurent Boulanger

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 27

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 27

But before interrogating any of Tracy’s neighbours, I wanted to have a chat to Mrs Noland. Although I didn’t want to jump to any conclusion at this early stage of the investigation, I knew homicide was often a crime of passion committed by a person usually well-known or related to the victim.

CHAPTER THREE

Mrs Noland agreed to be interviewed on the ninth floor of the St Kilda Road Police Complex, home of the homicide squad and part of the Crime Department of the Victoria Forensic Science Centre. The Homicide Squad at 412 St Kilda Road in Melbourne investigates deaths or serious injuries ostensibly resulting in death in connection with criminal violence or assault; accidents, including criminal negligence, vehicle, rail-road, aeroplane and boat accidents; suicides; drowning; any sudden death, or death which occurred under suspicious or unusual circumstances; and all deaths during confinement in jail or in a detention cell. The Homicide Squad works closely with the Arson Squad, the Robbery Squad, the Special Investigation Squad, the Burglary Squad and the Drug Squad, and collaborates with various other departments in the building, including the Fingerprint Branch, Document Examination and Traffic Offences.

Mrs Noland was not a suspect at this stage, and the basis of the interview I was to conduct - unlike an interrogation where questioning involves a person suspected of having committed a crime, having complicity in a crime or having direct knowledge about a crime - was to establish whether she had any information which I believed would be of interest to the investigation.

Prior to the interview, I managed to acquire some background on Mrs Noland. She resided at 13 Vincent Court in Albert Park, was forty-four years old, born in NSW, had completed four years of secondary education, and had never held a job in her life. She had no record of past problems with police or other legal trouble. According to Social Security records, she received adequate child allowance on the basis of being a sole parent. Payments were about to stop since she no longer had a child. I had no idea how she was going to make a living.

We were alone in a room especially designed for interviewing witnesses or suspects. To my eyes, the room was austere and sterile, not the ideal environment for interviewing potential witnesses. A green Formica table and three orange chairs stood in the middle, the walls were bare and painted white, and a video camera was mounted on one corner. Hardly a place to invite someone for a chat and a coffee.

For the past twelve months, I tried to explain to the Homicide Squad that transforming the interview room into a pleasant environment would produce different results. I found interviewees nervous and unwilling to cooperate fully. I was convinced that a room designed as a business office, with fish tanks, and pictures on the walls - other than police posters about doing the right thing - and other furnishing would produce the desired attitude with people. But traditional thinking and older police officers knew better and didn’t want to listen to any suggestions from some female PhD who trained in the USA.

I had to make the most of what I was being offered.

Two cups of coffee sat on the table, untouched.

Mrs Noland looked the same as when I first met her. Her face was carved in stone, and she wore the same dark lipstick. She avoided eye contact as much as she could, resulting in me feeling slightly uncomfortable. Interviewing was not something I particularly enjoyed doing, but it was something I was good at. I read her her rights and began the tedious procedure with the video camera rolling.

‘Did you have any problems parking?’ I asked, trying to break the ice.

She stared at me for a few seconds, looked down at her hands and said, ‘No.’

‘Mmm... I always find it difficult to park around here. Where did you park?’

She gave me another look. ‘You gonna get on with it or what?’

Well, sorry for being human. Fine, I thought, you want to play it rough.

‘Do you have any idea who killed your daughter?’ I asked bluntly.

Her eyes locked into mine. ‘No idea. This is a big, friendly neighbourhood. Kids always play with one another.’

‘Have you seen any grown-ups in the area?’

‘No one who’s not supposed to be there.’ Her tone of voice was non-committal, and I could tell she only wanted to get the hell out of here.

‘Look, Mrs Noland, I know losing a daughter is hard, and I know how you must feel right now, but you don’t seem to be willing to talk much. We’re on your side. If you don’t help us, we can’t help you.’

‘Do you have kids, Ms...?’

‘You can call me Kristina. And, yes, I’ve got a twelve-year old boy.’

‘How would you react if someone killed him?’

I stood still for a few seconds. ‘To be honest, I’m not sure. I’d probably be angry, depressed, I don’t know.’

‘Exactly. I’ve haven’t had the chance to practice this event. It wasn’t a subject taught at high school. So if you feel I’m being irrational, it’s because it’s my first time.’

I swallowed, wondering if there was more to it than she was telling me. Not the type of response I expected from a grieving parent. ‘Mrs Noland, did you have any reasons to want your daughter dead?’

‘Of course not, but other people might have.’

‘Were you angry at her?’

‘No.’

‘Did you fight at all?’

She pursed her lip. ‘We had words now and then, but it doesn’t mean I wanted her dead. Don’t you ever have a disagreement with your boy?’

‘Sure, I do. But did you ever hit Tracy?’

‘Hit? I’ve slapped her once or twice. But that doesn’t make me a murderer.’

‘Of course it doesn’t.’

‘This questioning is absolutely ridiculous. Why don’t you go and find who really killed my daughter?’

I sipped from my coffee cup. ‘Mrs Noland, all I’m trying to do is eliminate the obvious. In cases like these, it’s often the parents who kill the child. If I’m going to spend time and energy out there, I want to make sure I’m on the right track.’

Her eyes circled the room for a few seconds.

‘I haven’t killed my daughter,’ she retorted. ‘That’s all you need to know. I’m leaving.’

She stood and left the room.

I looked up to the video camera and shrugged.

Ten minutes later I met with Frank in the same room.

‘Goosh is pissed with you,’ Frank announced, as he circled the table, deciding on which chair to sit on.

‘So? Isn’t he always?’

‘Says he’s tired of you jerking him around and would like to talk to you whenever you can make yourself available.’

‘That might not be for a very long time.’

Frank took a chair opposite me. ‘What’s the story with her?’ he asked, obviously referring to Mrs Noland.

‘She seems very defensive and short-tempered,’ I began. ‘Kind of an unusual reaction. I expected her to break down at some point, but she didn’t.’

‘Do you think she did it?’

‘A bit premature at this stage, but nothing would surprise me. Maybe she didn’t do it so much herself, but got someone else to do it. Contract killing is becoming extremely popular, especially to solve family problems. All she had to do was establish a solid alibi and bingo.’

‘What about her husband?’

‘Checked the files. Doesn’t have one. She’s been a single mother since the birth of her daughter.’

‘And where’s the father?’

‘Left one day without a word or a trace.’

‘Do you think we should get a warrant to search her home?’

‘There’s not enough to get warrant, and I don’t want to scare her off. Maybe she didn’t do it. And if it is her, she’s not going to help us with anything. I’d like to talk to the neighbours first. See what they think. Maybe they saw something. Maybe they can tell me about the mother-daughter relationship. In a couple of days, she might come to accept what has happened and decide to cooperate.’

I looked at him without commenting.

He went on, ‘Maybe she killed the husband too, who knows?’ He scratched the back of his neck. ‘Anything else I should know?’

‘Yeah. She doesn’t have a driver’s license nor a car. If she killed her daughter, someone had to help her bring the body to the lake.’

Vincent Court, where Tracy Noland lived, was well-maintained, filled with Victorian-style houses, manicured gardens, expensive cars and not an adult soul in sight, only a bunch of kids playing down the end of the court.

I parked my car two houses down from the entrance of the street and checked myself in the rear-mirror. Satisfied I looked better than I felt, I stepped out of the car, clipped my photo-ID to the breast pocket of my navy sports jacket, and assessed my surroundings.

At 5.45 p.m., most people were home after a long day at work, unwinding in front of the television or enjoying time with their family. I felt like the big bad wolf who was going to intrude into everyone’s privacy, but life gave me no choice. I promised Tracy Noland’s mother I would do my best, even if it meant annoying the hell out of ordinary citizens.

Although I didn’t expect any dramatic encounters, not so early in the investigation, I tucked my .380 semi-automatic between my belt and the small of my back. It amazed me how quickly I depended on the gun to make me feel protected. I could honestly understand women in America who refused to walk alone at night without a piece. It was total lunacy, especially when one considered all the trigger-happy, feeble minds who carried weapons around, not to protect oneself where protection was freely available. There were those who argued that carrying a gun could potentially give my assailants the opportunity to kill me with my own weapon, but I’d like to think I’d still have a better chance of coming out alive than fighting with my bare hands against someone jabbing a knife at me. Morally, I felt uneasy about carrying a gun, but in the real world, morality didn’t always go hand in hand with survival.

Before knocking at someone’s door, I decided to have a quick chat to the kids who where playing at the end of the cul-de-sac. From a distance, they looked Tracy’s age, and according to Mrs Noland, Tracy used to play with some of the kids in her street.

I walked casually, as if I belonged in the neighbourhood, but psychologically, I was bouncing from one foot to the other.

The group of kids consisted of three boys and two girls - the boys wore knee-length basketball shorts with oversized T-shirts and Nikes; the girls wore cute little dresses, one green and one red. Some could have been brothers and sisters, I couldn’t tell.

The evening was warm and pleasant, making it ideal for kids to play outside instead of spending time in front of the box.

By the time I was five metres away from the group, I could feel them sensing my presence. Their chatting had turned to whispers, and it was clear I was trespassing.

I paced towards the children and forced a smile.

‘You guys hang around here?’ I asked, injecting warmth in my tone.

They nodded in unison without a word.

‘Oh, that’s cool,’ I said, as if surprised.

Kids’ language was different from grown-ups’. Everything was cool and dude and digging. I knew because my son Michael hung around with other kids of his age, and when they dropped in at home once in a while to empty the contents of my fridge, they spoke this foreign language.

‘I work for the cops. I’m just talking to people about Tracy Noland. Any of you knew Tracy?’

They looked at each other, and one of the boys, a redhead with more freckles than a poppy-seed bun, came forward.

‘You really a cop?’ he asked, his green eyes showing genuine interest.

‘Certainly am.’ I unclipped my ID from my breast pocket and handed it over.

He scrutinised the plastic card. ‘What’s the V-F-S-C stand for?’

‘Victorian Forensic Science Centre.’

He licked his upper lip and said, ‘Wow, cool, like an X-Files kind-of-thing?’

The other kids began surrounding me, passing my ID card from one to the other.

‘Sort of. I don’t do alien abductions, but you never know.’

One of the girls, blond hair, blue eyes, the one with the green dress, stood in front of me. ‘I’m Chelsea,’ she said, extending her hand. ‘I knew Tracy.’ I shook her limp, moist hand.

‘Yeah, we all knew her,’ the redhead added.

‘Yeah, she used to hang around here, but not with us. She was kind of by herself all the time,’ one of the other boys added.

Then the red-head: ‘We didn’t really like her. Never talked to us. She thought she was better or something. Treated us like we were kids.’

‘Anyone who knew her well?’ I asked.

‘Yeah,’ Chelsea said, ‘she used to hang around this guy. Don’t remember his name. He was older.’

‘How old was he?’

She looked at the others for some kind of suggestion.

‘Around seventeen,’ she said, and the others nodded their approval.

‘And you’re sure you don’t know his name?’

‘Nope.’

‘Do you know where he lives?’

‘Yep. Number twenty-two. That’s that one down there.’ She pointed to the other end of the court, towards the T-intersection, but it was too far for me to see anything. I removed my notebook from my pocket and jotted down the information.

‘Anyone else she used to hang around with?’

‘Not that I know of.’ To the rest of the group: ‘Guys?’

‘Don’t know.’

‘Nope.’

‘Nope.’

‘Nope.’

It was kind of weird watching these kids answer my questions as if they had one brain shared amongst them. In a way, it made me envious because I never experienced close friendship when I was a child until my last year of high school, when I met a girl named Evelyn Carter who went on to university with me but ended up choosing a career as a high-class prostitute. My parents were always moving from one place to another, making it impossible for me to establish meaningful relationships. Every year, I moved to a new school, saw new faces, faced new expectations. I admit the first time or so, it was kind of fun, but after a while, the novelty wore off and depression settled in. I concentrated on my homework instead, spending my lunch time hunched over newspapers and books.

I removed a bunch of business cards from my handbag and distributed them around.

‘If you guys remember anything about Tracy, like anything at all, I’d like you to give me a call.’

They all stared at the cards as if I had just handed out fifty dollar notes.

‘And we can call you any time?’ the redhead said.

‘Any time.’

‘Wow, cool.’

The first house I chose was elevated and had a pretty front veranda and rose bushes in the yard, enclosed by a green picket fence. I climbed the steps to the veranda and straightened my jacket.

I knocked twice on the door, my stomach churning. I was used to talking to people I’d never met before, but this time it would be different. I anticipated everyone in the street had learned about Tracy Noland’s death and would still be upset by it. And that made me more nervous than usual.

The advantage of conducting interviews so early on was that everyone would be willing to help, to feel they’ve done their part in aiding the investigation. Also, if anyone did see something, then their recall of events would be more accurate than if I conducted interviews in another week. I was expecting the customary answers; how Tracy was loved by everyone, how intelligent, beautiful and bright she was; and how they were all going to miss her.

The door opened, and I introduced myself to a forty-something woman dressed in grey tracksuit pants and an apron with ‘mum’s kitchen’ printed in large block letters on the front, overlapping onions, tomatoes, meat and a large carving knife. She told me her name was Susan Griffin.

‘Come in,’ she said, opening the door fully. Her brown hair was tied in a knot, and she could have done with ten kilos less. ‘Excuse the mess. I was making dinner. The kids have gone to play tennis and Darren’s still at work. Won’t be back until around six-thirty. Maybe you’d like to talk to him then, but he spends all his time at work, so he wouldn’t really know much about Tracy.’

I followed her down a wide hallway where arched corbels, ceiling roses, a candelabra light fitting and blue carpet set the tone.

Packets and tins of food lay all over the kitchen table, and something was on the boil. Stock aroma filled my nostrils, reminding me how hungry I was. The kitchen was spacious with wooden bench tops, a slate floor, timber cupboards, built-in dishwasher, stove and microwave and plenty of storage space.

‘I’m making beef goulash,’ Susan said, clearing some of the mess from the table. ‘You wanna a cuppa of something?’

‘Actually, I won’t be taking too much of your time. I’ve got to interview everyone in the street.’

‘Sure.’ She paused, puzzled for a few seconds and went on, ‘What a terrible thing to happen to a child. I’m not going to miss her, but still, that was not a nice way to die.’ She saw my inquiring glance and added, ‘Oh, don’t get me wrong. I didn’t want the girl to die or anything, but the few times she came over, she was a real little bugger. Complained about everything. Always fought with other kids in the street. Had a mind of her own, and, God, did she know how to use it. She was so miserable, kind of broke my heart. I never understood how someone so young could be so old.’

Her comments took me by surprise. It never occurred to me that the girl was going to be unpopular. In the back of my mind, I had associated her death with someone cute and kind and sweet, like all the pre-conceived ideas society had about little girls.

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim