- Home

- Laurent Boulanger

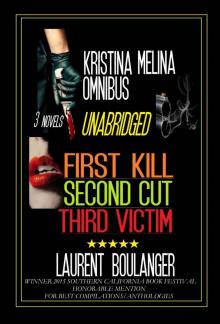

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Page 28

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim Read online

Page 28

‘Was she in trouble at home?’ I asked.

‘Not that I was aware of. Her mother was nice, though. But the other neighbours, they’ll tell you the same thing. She was not a nice kid, and no one wanted her to hang around. I’ll be surprised if anyone says anything different.’

‘Do you know why she was like that?’

‘Don’t know. You know what it’s like. People have all kinds of personalities, and you can see that from the time they’re kids. I guess if Tracy ever grew up to be a woman, she’d have been a real pain to live with.’

In the back of my mind, I disagreed with Susan, but I didn’t feel like arguing. It was too early at this stage to figure out why Tracy Noland had an attitude problem. And it was certainly a bit premature to conclude she couldn’t have changed. As a child, I always sulked and never spoke to anyone. My parents had branded me a problem child, although I’d rather have believed they were problem parents. But I didn’t grow-up a misfit, or someone who had a grudge against the entire human race. Maybe Tracy had problems no one really understood or could help her with. Maybe she’d given up on finding someone to listen. And if she was still alive, maybe she would have found that person or sorted herself out one way or the other, like most of us did eventually.

I shifted from one foot to the other and said, ‘Did she have any friends at all?’

‘Nope. But then, if she did, I wouldn’t know. She used to hang around the far end of the street. I only saw her now and then. I’m probably not the best person to talk to.’

I took down her phone number and thanked her for her time.

I visited another two homes after that, which also proved fruitless. No one really knew the girl. They were working people and only had time to mind their own business.

By the time I finished visiting my fourth, it was 10.34 p.m., and I decided it was too late to conduct further interviews. Most people would get annoyed if I knocked at their door late at night. I know I would.

I decided to leave the rest of the inquires for the following day.

Bright and early on Thursday the 18th December, I made my way to the VFSC in Macleod. The traffic was bumper-to-bumper chaos as usual, and it took me an hour and twenty minutes to drive all the way from St Kilda.

The VFSC was located next to Macleod Secondary Technical College and close to La Trobe University Bundoora Campus, where a Graduate Diploma in Forensic Science was offered to science graduates.

I turned left into Forensic Drive. A large blue sign with ‘Victorian Forensic Science Centre’ by the side of the road told me I was at the right place. The centre was surrounded with grass and bushland.

I drove past a blue, high steel gate and glanced at the security camera attached to the building. A ten-kilometre speed limit sign ordered me to slow down.

The main building was a brown-creamy colour. Gum trees lined the car park.

I parked in the main car park, between a red Toyota Cressida and a Ford Laser, and made my way to the main entrance, where I was greeted by glass sliding doors and a foyer which looked like a mini museum with its historical photographs, awards and trophies.

After clearing myself with Liaison, room C47, I went straight to Frank’s office at exactly 7.54 a.m. I had to meet Dr Main at the mortuary by 9.00 a.m., and I hated the thought of being late. He was going to run over the autopsy report with me.

Frank Moore was sipping a mug of freshly brewed coffee when I walked into his office. He looked as if he could have done with some extra sleep. His desk was clutter-free, and there was nothing on the walls other than his degree from RMIT.

We greeted one another, and then he told me Goosh wanted a progress report on the investigation. Christ, we’d only found the body twenty-four hours ago, and already he wanted me to explain what was going down. I swear to God, this man’s existence was designed to make my life purgatory.

Frank opened a cream manilla folder in front of him and lay it flat on his desk. He looked up and raised his eyebrows, a signal for me to go-ahead.

‘The kids around the area where Tracy lived seem to think she was kind of a loner,’ I said, pressing my buns into an orange, injection-moulded chair. There was a chill breeze from the air-conditioning, a nice change from the day’s forty-two degree temperature.

Frank looked up and eyed me in a way I couldn’t figure out. It was as if he was trying to shed some light on the comment I’d just made, but somehow he seemed lost in his own world.

He pursed his lips for half a second and said, ‘Well, you have to ask yourself why. Where do kids learn most of their behaviour from?’

‘Home, of course.’

‘That’s true. So, if a child’s got a problem, then you have to look at the source. It a well-known fact that children learn to imitate behaviour and develop a sense of morality in the first five years of life.’

Gee, I thought, when did Frank suddenly became a child psychologist?

‘Sure, but Tracy Noland was twelve-years old. Surely by the time you begin primary school, there are factors which influence your behaviour other than your parents. A teacher, whether good or bad, can make a difference in the way you look at the world. What about other school kids? There have been known cases around the world of children who committed suicide after being bullied around by school mates. That type of influence on a child’s character can’t be ignored, nor pushed on to the parents.’

He puzzled at my response for a few seconds and said, ‘Okay, I agree. But I believe that if a child has a problem, it’s always a parent-related problem. Jeez, you’ve done all this psycho-crap at university. You know that ninety-nine percent of people who have problems adapting to society have had problems with their parents. If a child lets himself be bullied at school by other kids, then surely it’s the way he’s been brought up which is going determine how he will cope with the situation.’

It was hard to argue with Frank, because he was right. I’ve never met a maladjusted person who didn’t come from a dysfunctional family. But was there such a thing as a non-dysfunctional family?

I shifted on my chair, realising I was going to be late for this morning’s autopsy at the VIFM. ‘Okay, so, maybe she did have problems with her mother. It doesn’t mean she killed her. Most people have problems with their mothers. I bet you had problems with your mother. Does this make every mother a killer?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘No, not directly. But you’re implying it. You’re pushing me into a corner. You’re trying to make me say the reason Tracy was a problem child was because she was going through hell at home. You want me to confirm her problems at home were the reasons why she was killed. And I don’t think I can agree with you. It’s far too early to make this type of hypothesis. You’re closing your eyes to other possibilities.’

‘Yeah, well, I like to think things are black-and-white. Why do you people always look for complications when everything can sometimes be so damn obvious?’

I told him about how the kids in the street told me about the seventeen-year-old-or-so Tracy used to hang around with.

‘I still think she did it,’ he said, refusing to consider what I’d just said. He closed his manilla folder instead.

I stared at him for a few seconds, wondering if he deserved a reply.

Finally, without any warning, I stood from my chair and aimed for the door.

‘I’ll see you at the mortuary,’ I snapped angrily.

CHAPTER FOUR

I met with Dr Charles W. Main in his office at 9.24 a.m., late for my nine o’clock appointment. He hadn’t sent me the autopsy report on Tracy Noland and had suggested by phone the previous night that I come to get a copy at the VIFM.

‘I’ve got some things I’d like to discuss with you,’ he said when I called him on my mobile phone on my way to South Melbourne to inform him I would be late.

I parked in the VIFM car park and entered the blue-grey building complex through a glass door. I showed my ID to the front desk and went down a corridor

and straight to Dr Main’s office.

Before I had time to greet him, he said, ‘So, didn’t have the stomach for the autopsy?’

I felt heat on my cheeks. ‘I never wanted to be a doctor, and watching dead people being split open is not my idea of a good time either.’ I also didn’t want to explain to him the backbone of every decision I made. That was as much as he needed to know, I felt, even though there wasn’t much more I could have added because it was the truth.

He did a quarter turn on his chair and said, ‘It’s just that you were supposed to be present at the autopsy. You realise your departure from the procedure might cause some problems later in court?’

I nodded embarrassingly, aware that some god-damn defence attorneys would do their best to discredit everything we ever collected as evidence to mount up a solid case. Not to mention that my reputation would be on the line, and some smart alec would suggest that I sit in a few autopsies just to toughen my stance.

‘I really didn’t mean to walk out. I was sick. What was I supposed to do? Throw up all over your work?’

He smiled, making me glad he had a sense of humour.

‘Okay, don’t worry too much about it. We’ve got the entire autopsy on videotape.’

He reached for a twelve-by-fourteen inch yellow envelope, which contained all the paperwork, photographs, legal identification records, fingerprint cards, and autopsy report to date. ‘I’ve finished the preliminary autopsy report. I’m still waiting for analysis on the stomach contents. Other than that, I can already confirm a few things, but this is only preliminary observation.’

I nodded for him to go on.

‘Well, I’ve found no major bruising, laceration or any other kind of injuries on her body, which you would have heard me mention the other day during the autopsy, if you were listening. Other than that, I’d say she died of asphyxiation, lack of oxygen to the brain. Some bruising and slickness of skin in the mouth and nasal area support my findings. She was smothered to death. No doubt at this stage.’

‘So, poisoning is out of the question?’

‘Can’t confirm either way. I’m still waiting for the toxicology results. There’s nothing to say she wasn’t drugged prior to the killing. Maybe she was put to sleep first, that’s definitely a possibility.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Yes, actually. When I removed and opened the stomach to check its content, I noticed an unusual smell of rose water. The contents were just half-digested food; greens, carrot and chocolate.’

‘Any idea what the rose water smell came from?’

‘Once again, don’t know. Couldn’t find any indication. I did make a note of it in my report.’ He passed me the pages he’d removed from the manilla folder. ‘I’ve made a copy for you. As soon as I get the toxicology results, I’ll have them sent to you.’

‘Thanks.’ I was truly grateful that Dr Main had bothered with me, especially after I’d been such a nuisance to him the previous year when I broke into his office. Maybe if I’d asked him for what I wanted back then, he would have gladly given it to me, but at the time it felt as if I was on my own and no one would lift a finger to help me.

He flicked through some pages of the documents he had with him. ‘Note that the autopsy report is not complete at this stage. What I’ve given you is something to work on. Be aware that the final report and opinion might differ to what’s in there. I wouldn’t go and arrest someone just yet on the basis of what’s in this preliminary autopsy report.’

I acknowledged his comment by nodding.

I took the duplicate autopsy report, which he handed across the desk, flicked through its contents and thanked Dr Main for his time.

I spent the rest of the day going through the autopsy report. Dr Main had conducted a thorough examination of Tracy Noland, and other than the bruising in the mouth area and the rose-water smell in the stomach, nothing was suspicious, at least nothing which Dr Main hadn’t pointed out.

Late afternoon, I returned to Vincent Court where Tracy lived. Before going door-knocking for the second time, I decided to visit Mrs Noland to see how she was coping and also because I was a little curious. I didn’t like the way our interview at the St Kilda Road Police Complex had ended, and I was hoping we’d be able to hold another on more civilised grounds. I wasn’t sure whether she killed her daughter at this stage, not like Frank who always jumped to conclusions without waiting for enough tangible evidence.

I believed in the way our justice system worked, how someone was innocent until proven guilty. It certainly didn’t make it easy for the police, who had to accumulate enough evidence to be able to justify an arrest and mount up a case. But the police were here to help us with truth and justice, and the complexity of their work was to ensure an innocent people wouldn’t be sent to jail over something they didn’t commit. Even though at times there were too many on-going cases, it didn’t give police the right to speed up the process just because they wanted to get the work over and done with.

During my years of involvement in criminology, I had seen good cops and people who had no place investigating crimes. Their work was sloppy, and they had no interest in justice, only in advancing their careers and exerting their power. These people were giving the Police community a bad name, clearly undermining the reason they’d been employed in the field of investigation in the first place. And at times, I felt Frank was bordering on that type of behaviour, although I’d never be brave enough to tell him to his face. My idea of justice was not merely to brown-nose everyone above me, or in my case anyone who’d have something to say when my contract would be up for review, but to serve the people of this country, the survivors, the victims and those whose lives had been abruptly shortened by another human being.

When Mrs Noland opened the front door, she didn’t seem surprised to see me.

‘Come in,’ she said, while pushing the fly-screen towards me.

I followed her down the hallway with its arches, corbels and ceiling roses.

‘Would you like something to drink?’ she asked as we stepped into the kitchen.

‘Coffee would be nice.’

I commented on her home being nice with its pale-green carpet and pale tones, and she began a monologue about how the three-bedroom house had be re-stumped, rewired, re-plastered and partly re-plumbed five years ago. The fireplaces and high ceilings had been reinstated, highlighting its Victorian heritage. The kitchen was modern and very functional with plenty of cupboard space. A skylight above my head kept the room bright and cheerful. The kitchen opened to a living room, which opened to a courtyard garden, where I noticed a large covered deck area, a brick barbecue and parking space for two cars.

While she was busy filling two mugs of instant coffee with hot water, I said, ‘I talked to some of your neighbours yesterday. They told me Tracy wasn’t very friendly with the other kids.’

She didn’t respond, obviously waiting for me to make my point.

‘They said she spent a great deal of time by herself and with a kid down the road. He lives at number twenty-two.’

Without turning around, she said, ‘I know.’ Her tone had changed from warm and mellow to sharp and snappy. She didn’t seriously believe I came here for coffee and biscuits?

I pushed on. ‘Did you know the young man Tracy used to hang around with?’

‘No, but I’ve seen him with her now and then.’

‘And that didn’t worry you?’

She turned around and locked her eyes into mine, ‘Why? Should it have?’

I grabbed the mug of coffee she handed me. ‘Doesn’t it strike you as strange that a seventeen-year old boy spends a lot of time with a twelve-year old girl?’

‘Should it? No one else talked to her.’

I didn’t know if she was playing me or was truly naive.

I went on, ‘Well, I feel that if it was my daughter, I’d be damn worried.’

‘Well, you’re not me,’ she snapped, ‘and frankly there was nothing admirable about

Tracy. I’m sick and tired of people putting her on a pedestal when she was nothing more than a sulky child. It’s my daughter, and I’m devastated that she was killed, but she wasn’t the angel you’re trying to make her be. All I want you to do is find the killer and stop poking at me. Just because I’m a housewife, you think I must be dumb. I know what you people are playing at. You think I did it, so you’re going to bombard me with all those silly questions until I crack under pressure and confess. Well, I tell you now, you’re wasting your time. I didn’t kill her, so you better start looking somewhere else.’

I stood speechless with my mug of coffee untouched. I had never been certain that Mrs Noland had killed her daughter. But her relationship with Tracy seemed somehow unorthodox, not what I would call in my books a typical mother-daughter relationship. Now I more or less understood where Frank was coming from. Her defensive attitude didn’t portray her in the best light. If I hadn’t known better, I’d think the next thing she’d tell me would be that Tracy deserved to die.

I sipped a mouthful of coffee while thinking carefully about what I was about to say next. I really wanted to get to the bottom of this, to clear the air and get everything out in the open. Whether she killed Tracy or not, making her an enemy would only complicate the investigation.

‘I didn’t mean to offend you, Mrs Noland,’ I said. ‘It’s just that with cases like these, we always have to look at the parents of the victim first. It’s a procedure we must consider before pushing further. Surely, you can understand that.’

‘I understand,’ she said as if cued, but not giving away what was really on her mind.

‘There’s no indication that you’ve killed your daughter. All I’m trying to accomplish at this stage is to establish a list of people who knew her. It’s unlikely, I believe, that she was killed by a complete stranger. It does happen, but in the majority of cases I’ve worked with, the victim has always been known to the killer.’ I took another mouthful of coffee. Then: ‘In your opinion, do you have an idea of who might have been interested in getting rid of your daughter?’

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim

The Kristina Melina Omnibus: First Kill, Second Cut, Third Victim